The Future Challenges of MEES

Andrew Cooper is a director at EVORA EDGE, Tom Marshall is a partner at Gerald Eve and Paul Henson is a partner at Irwin Mitchell

The future risks associated with the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards have cropped up in our conversations with clients more than any other issue lately.

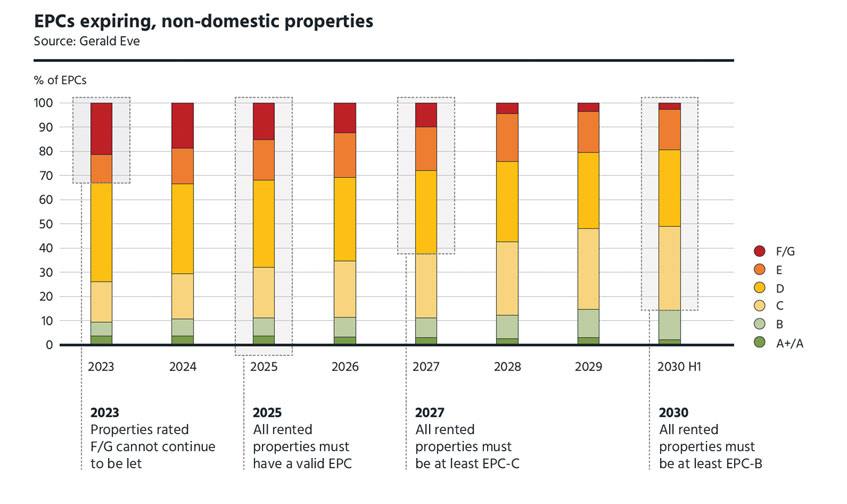

The reason, of course, is the government’s policy (as confirmed in the energy white paper, Powering our net zero future, issued in December 2020) to increase the energy efficiency threshold a commercial building must meet before it can be let. If legislated this will be a B EPC rating by 2030 – less than 10 years away (see box for more detail).

Of the circa 91,000 non-domestic EPCs lodged in 2019, only 15% were A+/A or B rated. In the last decade, it is estimated that less than 12% of all EPCs lodged were B or higher. This means the vast majority (88%) of non-domestic properties will need to be improved over the next 10 years (during the life of the EPC) to comply with future MEES requirements.

EPC data and proposed compliance windows to 2030 for non-domestic buildings

To add to the general confusion, the government recently consulted on the introduction of operational energy ratings for buildings over 1,000m². Confirmation is expected in the autumn (see below).

MEES obligations for landlords of commercial buildings

Confirmed obligations

Now: Landlords of non-domestic, private rented properties (including public sector landlords) may not grant a tenancy to new or existing tenants if their property has an EPC rating of band F or G, subject to any qualifying exemptions.

1 April 2023: If a non-domestic property is already let, landlords must not continue letting it if it has an EPC rating of band F or G, subject to any qualifying exemptions.

Likely obligations:

1 Apr 2030: Non-domestic properties must have an EPC rating of a B before being let, unless subject to exemptions (Energy White Paper, 2020). Consultation on implementation, exemptions and penalties now closed. Regulatory amendments due to come into force on 1 April 2025: See Powering our net zero future

Potential obligations:

2022/24: Mandatory operational energy ratings for buildings over 1,000m². This could include a proposed hybrid approach where landlords will still have an obligation to install measures that would meet a B EPC rating by 2030, but compliance would be checked as part of the operational energy rating process. Consultation now closed and decision expected in autumn this year. See: Introducing Performance Based Ratings in Commercial and Industrial Offices above 1,000m² in England and Wales

1 Apr 2027: Interim milestone of a C EPC rating. Consultation now closed and government response expected late June 2021. Regulatory amendments due to come into force on 1 April 2025. See Introducing Performance Based Ratings in Commercial and Industrial Offices above 1,000m² in England and Wales

How to meet the requirements

Securing a B EPC rating or a good operational energy rating will, in most cases, require fundamental changes to building services such as lighting, heating, ventilation and air-conditioning. This will require capital expenditure by landlords.

However, to determine the impact of this spend on asset value requires information in two key areas:

- What changes are realistic with regard to the building’s current engineering design and tenant use?

- How much of this spend can be reclaimed through service charges and how much is landlord investment? When does the money need to be spent?

In our experience, there are two tools that can help provide this information that are not commonly used for this purpose at the moment.

The first is a dynamic simulation model (DSM) of each building. The second is what we call the alternative planned maintenance report (APMR).

Building a dynamic simulation building model

Every EPC produced requires a building energy model to be built and there are two types of software used to generate these models – SBEM (simplified building energy model) and DSM (dynamic simulation model).

An SBEM model is built purely for the purposes of producing an EPC. A DSM is a model with far greater detail and accuracy. While it can generate an EPC, it can also be used for a wide range of asset management purposes, such as BREEAM calculations, climate change modelling and productivity metrics. It can also be adapted to undertake design work or stress-test interventions to help secure improved operational energy ratings, such as NABERS UK.

DSM models are more expensive but offer flexibility and long-term asset management capability. It is not easy to convert an SBEM model to a DSM model, but it can be done by a skilled and suitably qualified modeller.

DSM model simulations, when done in consultation with contractors and engineers, are also useful for sense-checking sustainability recommendations.

For example, many organisations may have a blanket recommendation to switch to LED lighting. This is always a good idea, but it may have a range of knock-on effects, such as a need for increased heating in parts of the building. This in turn impacts the overall EPC rating. Therefore, any potential energy savings resulting from improved lighting needs to be considered alongside potential increases to heating bills and even, potentially, plant sizing.

The PMR and the ‘alternative PMR’

The real gap at the moment is linking the cost of sustainability strategies with the budgeting process for ongoing planned maintenance, usually through a planned maintenance report (PMR).

A PMR is a strategic asset management report. It provides the annual cost of repair and replacement of assets for the duration of the PMR term, usually 10 years. It is prepared by technical specialists in partnership with property managers and owners. Costs included in the PMR are typically recoverable through service charges, meaning the emphasis is on repair or like-for-like replacement. A PMR does not therefore typically include the cost of changes that would improve the long-term sustainability and efficiency of a building as these are not always easily recovered through the service charge.

A way around this is to commission what we call an alternative PMR (APMR) alongside the PMR. This strategic document is aligned to the RICS New Rules of Measurement and includes the additional interventions and spend required to achieve a stated goal (either a target EPC rating or net zero carbon pathway).

Impact on value calculation

The difference between the PMR and the APMR cost plan(s) is the potential impact on a property’s value. This represents the additional sum of money that needs to be spent to realise a target.

We call it the “impact on value statement” and it can be used to support an RICS qualified valuer with the valuation processes.

By following this approach, it is possible to put in place a robust action plan to deal with MEES risks now, despite the uncertainty around the government’s future statutory approach. We have summarised the immediate tasks to be actioned below.

Proposed tasks for managing MEES compliance and energy performance

- Obtain the current EPC model (not just certificate) and validate its result. For various reasons EPCs can be inaccurate or change according to updates in the EPC national calculation methodology. This helps to accurately assess the level of risk faced.

- Convert the existing model to DSM or build a new model in DSM. Only use SBEM where the consultant provides a reason as to why DSM is not appropriate, and never use SBEM for anything regarded as investment grade and/or with a 5+ year holding strategy.

- Use the model to identify a pathway to ensure compliance with MEES or net zero carbon targets.

- Use the PMR to calculate maintenance, repair and replacement costs that are service charge recoverable. Commission an APMR to identify those additional costs required to meet MEES obligations or net zero carbon targets.

- Update the model whenever category A, A+ or B work is undertaken to ensure the information in the model is always accurate. This ensures the model can be used as a decision-making tool at any time and EPCs can be produced whenever required without the cost of rebuilding the model.

As lease lengths shorten and companies look to improve their ESG credentials, the impact of MEES legislation is likely to become an even bigger issue than it is currently and it’s important that property owners start putting their plans in place now, rather than leave it until late into the 2020s.

It is also essential that managing agents and property advisers work alongside building services engineers and lawyers to navigate through this complex and changeable terrain. Only through collaboration and joined-up thinking can we accelerate our progress on sustainability, which has been painfully slow in the property sector to date.

Download the authors' full guidance note here Energy Performance in Non-domestic Buildings

A copy of this article first appeared in Estates Gazette